Entirely up to you as to whether you want to do this one. I find it benefits me a lot personally, but your comic might not even be in colour! And even if it is, you might not be as overly picky about them as I am ahaha

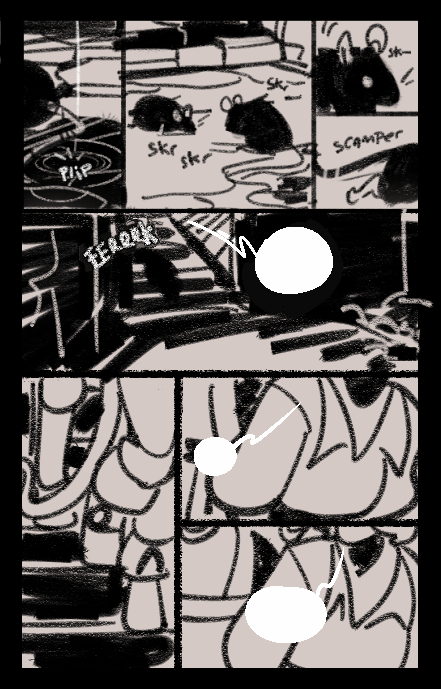

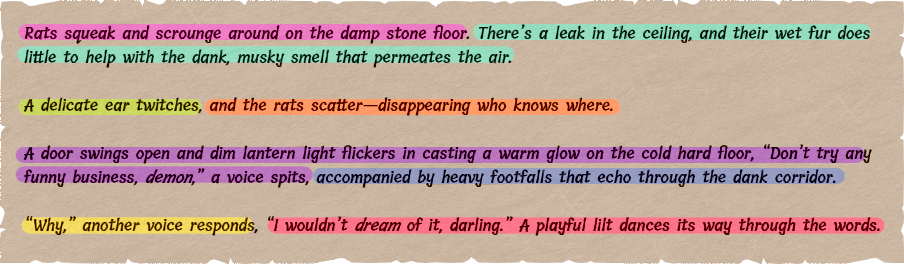

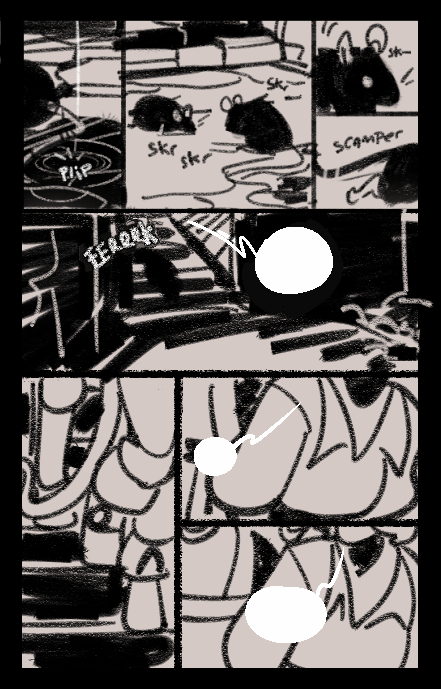

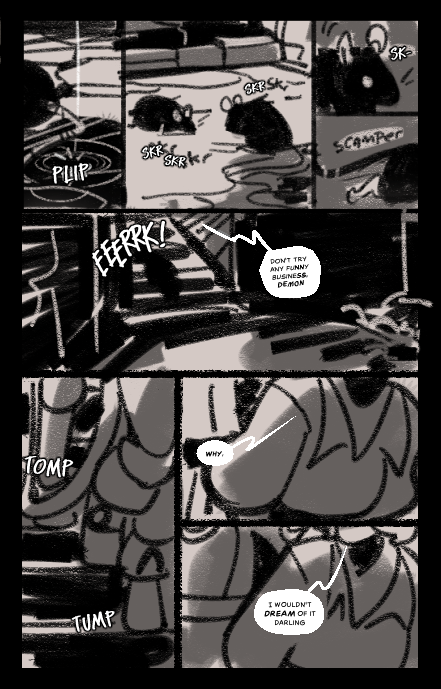

Rats squeak and scrounge around on the cold, damp stone floor. There's a leak in the ceiling, and their wet fur does little to help with the dank, musky smell that permeates the air.

A delicate ear twitches, and the rats scatter—disappearing who knows where.

A door swings open and the dim lantern light flickers in casting a warm glow on the cold hard floor, "Don't try any funny business, demon," a voice spits, accompanied by heavy footfalls that echo through the cold corridor.

"Why," another voice responds, "I wouldn't dream of it, darling." A playful lilt dances its way through the words.

I write my script in prose format, but it really doesn't matter what it looks like—just that you write one at all! It's super important in my opinion!

I read a tweet once, it was aimed at indie game devs:

It's about the common tendency that independent creators have of starting projects, then getting a new idea that seems so much more exciting than the one that's currently being worked on.

But more than that, it's the concept that while an idea is there in your head, it's filled with infinite possibility—there's so many different things that it could be, because it isn't anything at all yet.

But when you start working on it, it ceases to have infinite possibility because suddenly, it already is something.

You could not write anything out at all and jump right into drawing a comic. I've done this many times before—I'd be like, "it's only going to be like four pages, I don't need to write a script for this!"

But, in going from idea straight to comic, all those infinite possibilities have to suddenly become...just one. And if you find that you didn't pick the best possibility for that page or that panel...

Take it from me, it's much harder to rearrange panels you've drawn and keep everything fitting on that one page, than it is to rearrange sentences in a text document!

So, I think, it's worth it to confront the different ways you could approach an idea as early as possible with the least amount of commitment to one way.

Write it down, feel your idea out!!

This is, obviously, a section from a larger script, but I cut it here because it felt like just enough to fit on one page without being too much.

It ended up being 8 beats which, in my experience with the dimensions I work at, at most on a single page I can only fit about 14 panels. That's really pushing it though, on average my pages will only have 7-8! This one being 8 hits that nice comfortable zone

I prefer to keep the higher panel counts for high activity pages—the more panels you have, the smaller they have to be and thus the less time readers will be focused on them.

If there's a lot of high action content happening, lots of smaller panels will create that du-du-du rapid fire high action feel, but if it's a low action page, having lots of panels might make things feel hectic and rushed when it doesn't want to be!

Too few panels though, and things will feel very slow. I have some pages that only have one to four panels, these are during very slow moments when I want there to be a lingering feeling.

Just something to think about when dividing up your script! For me, 8 is a nice average not-too-much is happening, without being too slow to progress things.

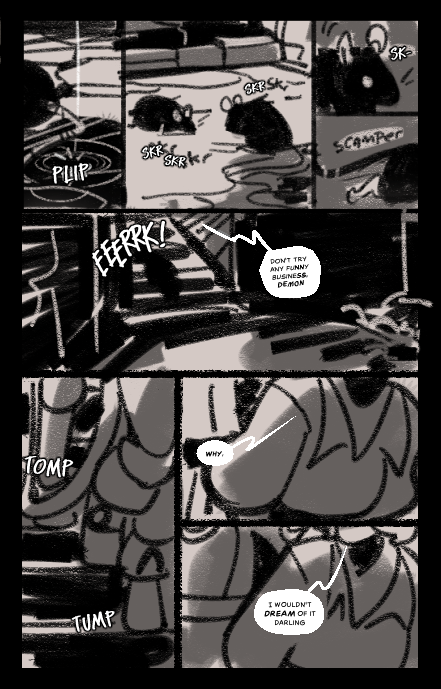

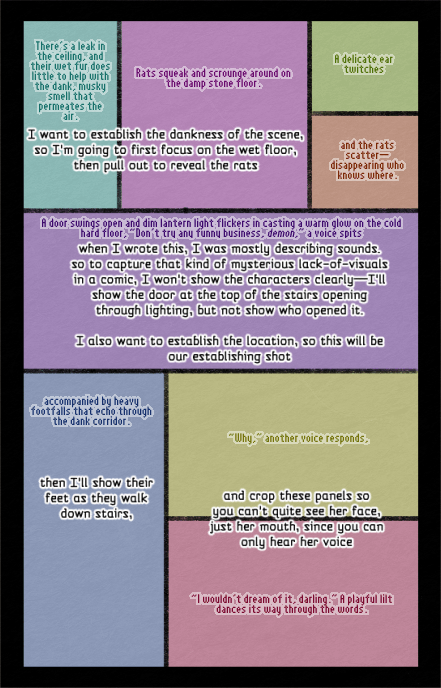

The page has been divided into 8 panels, colour coded to match the previously colour coded script, with the relevant lines inside of each panel. Over the top of these panels are captions explaining my thought process, which read as follows...

First row (4 panels): "I want to establish the darkness of the scene, so I'm going to first focus on the wet floor, and then pull out to reveal the rats."

Second row (1 panel): "When I wrote this, I was mostly describing sounds. So, to capture that kind of mysterious lack-of-visuals in a comic, I won't show the characters clearly—I'll show the door at the top of the stairs opening through lighting, but not show who opened it. I also want to establish the location, so this will be our establishing shot."

Third row (3 panels): "Then I'll show their feet as they walk downstairs, and crop [the last two] panels so you can't quite see her face, because you can only hear her voice."

So when I'm thumbnailing my comics and figuring out the panel layout, I don't think of panels as boxes I'm arranging on the page—instead, I'm splitting the page up into sections.

It's worth bearing in mind, as you read a comic, panels in a row will be read one after the other, but when you go to an entirely new row, your eyes have to go all the way back to the other side of the page.

That means there's a slight disconnect between the panel on the right side, and the next panel on the left side.

If a series of beats are connected to each other, I try to keep all of them on the same row, and if a beat is not very connected to the other beat before it, I might put its panel onto a new row. As well, I'll split a panel in half horizontally if they're directly connected to each other, or if they're happening at the same time!

But, grouping beats together, then dividing the page into rows that can hold these beats together is how I approach panelling a page

For further reading, I recommend picking up Scott McCloud's Books "Understanding Comics" & "Making Comics"! He has a lot of very useful things to say about the different types of panels, how the progression of time works in comics, and stuff like that... essential reads for anyone making comics!

I'll let you in on a little (not so) secret—the version of Heart of the Storm that ultimately went live in May of 2024 is not the first attempt I had at drawing it.

My first attempt at drawing it was in 2020, and that version never got released to the public... because I went into it with zero planning! No thumbnails, nothing. Before long I found myself incredibly frustrated with the pages I was drawing, but I'd drawn so much and reworking it all was incredibly difficult! Ultimately I stepped away from it to explore making comics differently with some low stakes fancomics.

I learnt a lot from these little comics, and critically with these comics I thumbnailed them and I wrote a script before I drew the final pages, something I was not doing before. I meant it earlier when I said I think it's important to figure out all the different ways to approach things early on... I was speaking from experience! A lack of planning made comics difficult and frustrating and the results were just not what I wanted.

So after a much more pleasant comicking experience by planning things out from the start, I decided that with HotS I should start again with a more concrete plan this time. And so I did, and I never regret it!

In writing, the common advice goes "show, don't tell," and this applies to many different aspects of writing, but especially to describing things. The other advice is to describe using all five senses—sight, sound, smell, touch, and taste.

With these experiments especially I discovered I prefer to write my scripts in prose format—one because I grew up reading a lot of books, but more importantly for two because I think this is just as important to do in comics as it is in prose, and writing it in prose first helps me make sure I think about these things.

This is not to say that I think you should write your script in prose—how you write your script is entirely up to you and your personal preferences! As I said earlier—what matters is that you write your ideas down in some form. But what I am saying is to think about the 5 senses while you write it, in whatever form that is.

Of course, we only really have sight and sound to work with in a comic, we can't describe the way something smells or how it tastes because we can only use visuals and the occasional onomatopeia, but how you choose to frame your panels will communicate different things!

Compare now then, the original page I was drawing in 2020, to the final page I ended up with:

I think it's safe to say that the redone page is more immersive. This isn't because I increased the panel count (indeed, there are many panels that I cut in the revision), but because I was more thoughtful about the panels themselves and what I was communicating with them!

The dank, musky smell and scent of damp fur may not be something I can tell my readers about in a picture—but if I focus on the puddles on the floor, and show the rats' wet fur... they'll feel how dank it is anyway.

So, while composing the panels in your comic, consider what you're communicating through them, and whether you're telling what happens, or if you're showing your readers what it feels like to be there and what your characters are going through.

It'll help you compose more interesting pages!

The most important thing to understand about thumbnails is you are not creating a finished picture, you are thinking about how you want to approach the finished picture, especially its composition. Thumbnailing is about thinking visually, so be prepared to erase things at any moment, as you might think of something better the next time you look at it!

Exactly how refined your thumbnails look is going to vary depending on your purposes and how much thinking you want to do in your thumbnailing pass. Myself personally, I like it if when I come to blow up my thumbnail to page size and start drawing the actual page to not have to think about a single thing, which results in my thumbnails doubling as a sketch and going through more than one pass. For most people, they'll have one pass and exclusively focus on planning the layout in their thumbnails.

Again, I said earlier "it's harder to rearrange panels on a page than it is words in a text document", and by this I mean when you draw a panel and then decide it would work better on the next page you now have to cut that panel from one page and move it onto the next, and now there's an empty space that you have to fill on the original page, and on the next page you now have to shift everything about and squeeze it in and move things around to make space for this panel....

That's a hassle!... Unless, you're working small and loose and nothing has been finalised yet, so you have the freedom to shift things about on the page without worrying about erasing things and filling the space. Let it be messy, you're thinking things through!

The key thing is that even though personally I do multiple passes with my thumbnails, they still begin with the same initial rough noncomittal phase where I can and will delete things without a second thought, and indeed even at their most refined I will still delete a thumbnail if I don't think it's working. You're not making a beautiful sketch, you're thinking about how you want to approach tackling the final page.

This is why I do multiple passes myself, I'm doing an awful lot of thinking upfront. As previously established, I started out doing zero planning and ended up with pages I hated, so now I do perhaps a little too much planning haha, but it works for me! I imagine for most people however, you'll be fine with a little less planning. Here's how my thumbnail passes breakdown:

In anycase as you can see, first I focus on how I'm going to layout the page and frame the contents of each panel, then I come to the value pass and I think about how I am going to utilise value on the page to guide the eye and provide clarity for foreground and background elements, and then if I do a colour script I think about how I'm going to utilise colour to set the mood and retain those values I established before.

The goal here is never to make a nice image, but to make something understandable and thought out. It's a plan of attack! By the time I draw the page itself, I know exactly what will go where and how I'm going to execute it. I'll admit freely, not every page I make is as meticulously planned as the rest, they don't need to be! The first few pages got special treatment as I wanted to make a good impression, haha! But while the final thumbnails may be rougher for some pages than others, once I come to draw a page, I always know what I'm doing with it, because I took the time to plan it out first.

I should also note that I don't thumbnail pages in isolation, and I don't recommend you do either! Thumbnailing entire chapters like I do is a slow process and one that won't suit everyone, but I do recommend that you thumbnail in groups of around 10 pages so you can shift things around between pages and take the time to get a feel for how they're read in succession.

In anycase, I hope that was enlightening! Best of luck with your own comics ❤️

EDIT (4th December 2024) :: I recently received a comment from one of my readers thanking me for the inclusion of the prose transcripts on Heart of the Storm as, having read this post, being able to see the prose that became the final page I drew helped a great deal in demystifying the act of translating words into a comic page. I hadn't even considered this, I added that for accessibility reasons! But that's such a wonderful side effect and I mention this here because if you'd like to see further examples, you might be interested in looking at some of the pages on my comic's website and expanding the transcript boxes underneath.

While I'm here, I'd also like to add that I love helping people get into making comics (evidently, why else would I write this!) so if you have any further questions about making comics you are more than welcome to drop a comment below or send me an email through my contact page. Or even an ask on tumblr if that's more your thing! Any question big or small is welcome, if I can't answer it myself I'm certain I can direct you to someone who can, and if I can help you get started I'd be delighted to assist :)

EDIT (23rd December 2024) :: I found some older files of mine, and having now since completed the page that I was showing in this post, I decided to revisit things and show some more in-depth breakdowns of my process and the various phases the planning phase goes through, as well as showing a comparison of before and after planning things out and the final result! I hope this updated version of the post will be even more insightful!

No comments yet!